| Audience | All |

|---|---|

| Prerequisites | Basic Linux Commands |

| Duration | 2 hour workshop (~2 hours of trainer-led time) |

Description

This workshop is planned to last for 2 hours. It is a live coding workshop and participants are expected to practice along with the instructor. Lessons will focus on using the command-line text editor, Vim, to create and edit files, utilizing for-loops for automation, using variables to store information, and writing scripts to perform a series of commands in a sequential order.

Learning Objectives

- Learning basic operations using the Vim text editor

- Capturing previous commands into a script to re-run with one single command

- Understanding variables and storing information

- Learning how to use variables to operate on multiple files

This workshop is designed on the model developed by the Software and Data Carpentry. The material on this page is part from the Software Carpentry Lessons

Setup

Download data-shell.zip and move the file to

your Desktop. Unzip/extract the file. You should have a

new folder called data-shell on your Desktop.

Open a terminal. If you’re not sure how to open a

terminal in your operating system, see the instructions

below. In the terminal type cd then press the ‘Return’

key. This step will make sure you start with your home

folder as your working directory. Later on, you will

find out how to access the data files in this folder.

Follow the instructions here to set up your operating system

Contents

Basic Shell Commands

Below is a key of the basic commands you should be familiar with in order to be able to follow this module.

## Commands

cd # change directory to "~" or to specified directory

ls # list contents of current or specified directory

man <command> # display manual for specified command

pwd # specify present working directory

echo "..." # display content in quotes on the standard output

history # display previous "historical" commands

cat <file> # display all contents of a file on the standard output

less <file> # open a buffer with the contents of a file

head <file> # display the first 10 lines of a file

tail <file> # display the last 10 lines of a file

cp <..> <..> # copy files or directories

mdkir # make a new directory/folder

mv <..> <..> # move or rename files or directories

rm <file> # remove a file or a folder (-r)

## Other

~ # home directory

. # current directory

.. # parent directory

* # wildcard

ctrl + c # cancel current command

ctrl + a # start of line

ctrl + e # end of line

Visit the sites below to see how bash commands are used

Shell Cheat Sheets

General Help

- man bash - run this at your command line to learn more about bash

- Google - Googling things you don’t know. Other people have probably had the same question.

- Learn by doing. There is no better way to learn other than by trying.

Introduction To Vim

Creating Text Files

There are two ways to create text files: using GUI text editors or command-line text editors.

NOTE: by “text editor,” we really do mean “text”. The editors can only work with plain characters, not tables, images, nor any other media.

GUI text editors

TextWrangler, Sublime, and Notepad++ are examples of GUI text editors. They have a Graphical User Interface that has buttons and menus that you can click on to issue commands to the computer and you can move about the interface just by pointing and clicking.

Command-line text editors

If we are working on remote computer (i.e. high-performance compute environments) we don’t have access to a GUI and so we need to use Command-line editors to create, modify and save files. When using these types of editors, you cannot ‘point-and-click’, you must navigate the interface using only the keyboard.

Popular command-line editors include nano, Emacs or Vim. These editors are available by default on any shell environment, including on high-performance compute environments (local or cloud).

Vim Text Editor

It is a powerful text editor with extensive text editing options; however, in this introduction we are going to focus on exploring some of the more basic functions. To help you remember some of the keyboard shortcuts introduced and to allow you to explore additional functionality on your own, the research team at the Harvard Chan Bioinformatics Core has compiled a cheatsheet

Vim Interface

Get into your work environment with cd and make a copy of the file notes.txt into a new document entitled

vim_notes.txt. Use vim to open the new document

$ cd ~/Desktop/data-shell

$ cp notes.txt vim_notes.txt

$ vim vim_notes.txt

Vim Modes

Vim has two basic modes that will allow you to create documents and edit your text:

- command mode (default mode): allows you to save and quit the program (and execute other more advanced commands).

- insert (or edit) mode: allows you to write and edit text

Files open with vim are automatically in command mode. To change to the INSERT mode, push the i-key and

notice the --INSERT-- at the bottom left hand of the screen.

Type a few lines of text:

While vim offers great functionality, it takes time to use, get familiar and learn the shortcuts.

After you have finished typing, press esc to enter command mode. Notice the --INSERT-- disappeared

from the bottom of the screen.

Vim Saving and Quitting

To write to file (save), type :w. You can see the commands you type in the bottom left-hand corner of the screen.

After you have saved the file, the total number of lines and characters in the file will print out at the bottom left-hand section of the screen.

Alternatively, we can write to file (save) and quit all at once. Let’s do that by typing :wq. Now, you should

have exited vim and returned to the command prompt. To edit your vim_notes.txt document, open up the file again

using the same command you used to create the file:

$vim vim_notes.txt

Change into the insert mode and type a few more lines (you can move around the lines of text using

the arrows on the keyboard). This time we decide to quit without saving by typing :q!

Vim Editing

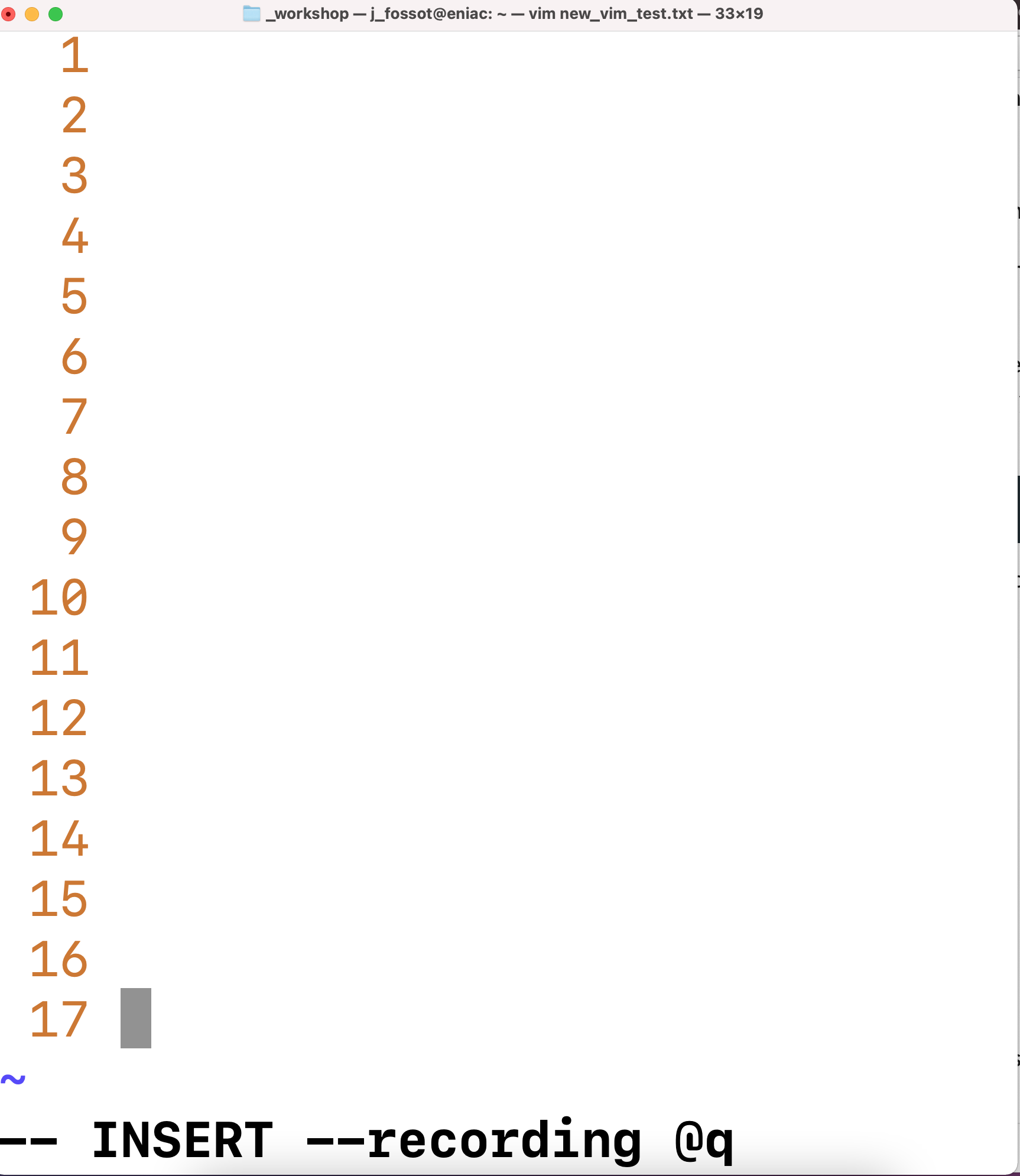

Create a new document new_vim_test.txt in vim. Enter the text as follows: vim new_vim_test.txt

Add line number to the document by switching to the command mode and typing :set number.

Save the document. If you choose to remove the line numbers later you can type :set nonumber

Vim has shortcuts (which are completely unituitive, but very useful as you get used to them over time). Check to see what mode you are currently in. While in command mode, try moving around the screen and familarizing yourself with some of these shortcuts:

| Navigation | Editing | Saving and quiting | |||

| key | action | key | action | key | action |

| gg | move to top of file | dd | delete line | :w, :wq | save, save and quit |

| G | move to bottom of file | u | undo | :q! | quit without saving |

| $ | move to end of line | Ctrl + r | redo | :set number | display line numbers |

| 0 | move to beginning of line | i, esc | insert and command modes | :set nonumber | not display line numbers |

Exercise

We have covered some basic commands in vim, but practice is key for getting comfortable with the program. Let’s practice what we just learned in a brief challenge.

- Open notes.txt, and delete line #2.

- Quit without saving.

- Open notes.txt again, go to the last line and delete it.

- Undo your previous deletion.

- Redo your previous deletion.

- Save the file and see whether your results match your neighbors.

Shell Scripts

Since we now know how to create text files in the command-line interface, we are going to use that knowledge to create a shell script and see what makes the shell such a powerful programming environment.

Simple Scripts

Let’s write a shell script that will do two things:

- Tell us our current working directory

- List the contents of the directory

First open a new file using vim:

$ vim first_script.sh

Then type the following command into first_script.sh file:

echo "Your current working directory is: "

pwd

echo "This is the content of your working directory: "

ls -lFG

Save and exit the file (:wq)

Use bash or sh to execute first_script.sh

bash first_script.sh

Execute the script in a different directory other

$ mkdir other

$ mv first_script.sh other

$ sh other/first_script.sh

More elegant way to execute the script

- open the file

$ vim first_script.sh - On the first line of the file write

#! /bin/bash - Step 2. indicates to the script where the bash executable is.

- Make the script executable with

chmod +x first_script.sh. - Execute in the current directory with

$ ./first_script.sh, and hit return . - Execute in the parent directory with

$ /other/first_script.sh, and hit return .

Did it work as you expected? Was the echo command helpful in letting you know what came next?

Bash Variables

A variable is a common concept shared by many programming languages. Variables are essentially a symbolic/temporary name for, or a reference to, some information. Variables are analogous to “buckets”, where information can be stored, maintained and modified without too much hassle.

Simple variable Lets assign 25 to num

$ num=25

Retrieve the value of num

$ echo num

What do you see at the command line? When retrieving the value stored in the variable, explicitly use a $ in front of it:

$ echo $num

Variables can also store a string of character values.

$ file=pentane.pdb

Passing Argument(s) to a script

- Argument(s) are passed to the script at the time of execution.

- Inside the script,

$1variable references the first argument$2variable references the second argument$nvariable references the nth argument$0is reserved and references the current script Change to the molecules directory

$ cd molecules

$ echo $file

Let’s try using the variable in a command

$ wc -l $file

NOTE: Variables created are system-wide, and independent of where you are in the filesystem. This is why you can reference it from any directory. However, it is only available for your current session. If you exit or close your Terminal, the variables you have created will no longer exist.

Example of Argurment passing to script

- Open the file

$ vim first_script.sh - Write the following line of code in the file

#! /bin/bash echo "This script was executed as: $0 " for filename in $1 $2 $3 do echo "Argument passed is $filename" echo "$(wc -l $filename) lines" doneExercise

- Reuse the $file variable to store a different file name, and rerun the previous commands.

Variables can store more than just a single value

The command below list all the files ending in .pdb in molecules directory.

$ ls *.pdb

Assign the output to a single variable

$ files='ls *.pdb'

Note the syntax for assigning output of commands to variables.

Check the output

$ echo $files

Let’s try the wc -l command again, but this time using the new variable files as the argument:

$ wc -l $files

Exercise

- Use some of the other commands you are familiar with (i.e.

head,tail) on thefilesvariable.

Repetitive Tasks

In the previous example all the files were saved into a single variable files. We could access files

content one at a time. This is called looping.

Looping is a concept shared by several programming languages, and its implementation in bash is very similar to other languages.

The syntax of (for) loops in bash is as follows:

for (variable_name) in (list)

do

(command $variable_name)

.

.

done

- variable_name defines (or initializes) a variable that takes the value of every member of the specified list one at a time.

- At each iteration, the loop retrieves the value stored in the variable.

- The commands indicated between the do and done are executed one at a time.

Example

for File in files

do

echo $File

wc -l $File

done

- The script writes to the terminal

(echo)the name of the file, - then the number of lines

(wc -l)for each file. - the number of items in the list (variable name) == number of times the code will loop through.

- Variable name does matter in the loop.

- Make the variable name intuitive, indicate functionality.

Optional Resources

The following are additional resources that you may find useful:

- Shell Scripting

- Ryan’s tutorial

- The Linux Command Line (Part 4: Writing Shell Scripts)

- Bash Guide

- Shell programming with bash: by example, by counter-example

- Networking